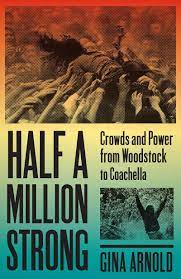

I read Gina Arnold long before I met her. When I was coming up as a music writer, in the ’80s, she was already an established critic, with bylines in Spin and the Village Voice. Somewhere in there — in between gigs with Rolling Stone, Entertainment Weekly, and a host of other publications — she also got her doctorate in modern thought and literature from Stanford University and has since turned her doctoral thesis into an astounding new book. Called Half a Million Strong: Crowds and Power from Woodstock to Coachella, it tackles all those things we know in our gut to be true — that feeling that we’ve found “our tribe” in music, the collective power of concerts — and analyzes them with the same perceptive take that she brings to criticism itself.

This week, with the passing of the Monkees’ Mike Nesmith, she and I got to talking. This is the result:

You Once Thought: The Monkees Music and Me.

One upon a time, not that many years ago, I was standing in a long line behind a diving board awaiting my turn when the Monkees came on the loudspeaker. It was 7 a.m. in the morning and I was sopping wet and freezing. The line was a very long line, made up of a lot of ladies over 50 competing at US Master’s Nationals. In one way it was a grim scene, but that all changed when the song came on. Immediately, the woman in front of me, my main rival as it happened, began jumping up and down. “I love this song I love this song!” she gasped, and began singing:

“Oh, I could hide ‘neath the wings

Of the bluebird as she sings

The six o’clock alarm would never ring” (she sang).

And I surprised myself by joining in:

“But it rings, and I rise

Wipe the sleep out of my eyes

My shavin’ razor’s cold and it stings!”

On the last line, the two of us looked each other right in the eyes, and literally shouted the lyrics at each other, as if they were (as is written above) in italics. And then, of course we burst out laughing. What a silly lyric! What a silly song! And yet! Was it? Because we had risen at 6 a.m. We had wiped the sleep out of our eyes. We had just used shavin’ razors, as one does before a diving meet…in short, it was weirdly apropos of our singular circumstances, but even if it hadn’t been, that song, sung right then, by two old ladies in too-tight bathing suits as the mist of the swimming pool rose around us, made a great song sound ever so much better.

And so of course it was the moment I thought of when I read the Mike Nesmith died last week, because it said something not only about the Monkees, but about popular music in general and its role in my life. I read a meme recently that said, “Art decorates place, music decorates space.” The music of the Monkees decorated my childhood, but they also decorate the present, as at the pool that day when they lifted the hearts of everyone present, even that of my biggest rival; when for a second they broke through some kind of space-time continuum and the air shivered and cracked as we all existed on the same plane in it, regaining our lost youth.

The Monkees break the bank when it comes to the number of deposits in their music appreciation account. You could conceivably be bored by the Beatles, and the Stones are questionable in a number of areas starting with their super creeper lyrics. But there are no possible pitfalls or fences around anything to do with the Monkees. There is nothing not to love about them…at least, not at this point. Back in the day, I imagine, there were a lot of guys who put them down for being manufactured — “The PreFab Four,” I heard they were called. But little girls like Jennifer (my rival) and I had no false ideologies to prevent us from loving the well-written music and the charm of their personas. And as time went on, others recognized it too. I remember feeling so validated when Paul Westerberg played “Daydream Believer” at a solo gig I went to in the 1990s, and I realized that it wasn’t just a song I liked when I was a little girl, but a song well worth liking now: a song that even Paul Westerberg liked. When he sang, “You once thought of me, as a white knight on a stead,” I got a big lump in my throat. That one word, “once,” just says it all, doesn’t it?

Clea’s new book, Hold Me Down, captures a little bit of this feeling — that sweet but melancholy emotion that beloved old music can conjure up; the uncomfortable sense that age is both the main fact of our life and also the least important. Her book is set in the present, but the characters have a lot of memories of an indie rock past — as do I, I should add: as do I. My own books about music – like my most recent Half a Million Strong, which is about why we loved to go to music festivals despite the fact that they are sort of dreadful — also recapture le temps perdue, but I wonder sometimes if I dwell too much on those things; if I should be moving on, if music should always, as I once used to swear, be new.

The closed world that Clea and I used to roam around in is no longer with us, and that is probably a good thing, not a bad one: everyone needs to make their own musical community, and if we all only turned to older tunes to do that, the air around us would get positively stale. That’s why I always think it’s odd when people drag their little kids to see the Rolling Stones or Bruce Springsteen. How could they ever experience what we did, through that music?

Anyway, I am not convinced that kids today create their identities around the music they listen to anymore – the ways they listen to it, and thus its role in their lives, is just so different than the way we did, that is, that Clea and I, and even Jennifer, my diving rival, did. But old music is still worth writing about, and celebrating, and musing upon, and remembering, isn’t it? Publishers seem to feel differently, but that’s my working theory at the moment. — Gina